Mining Town: Part I

Lewis Rubenstein and the Art of the 1930s

By

Daniel Blake Rubenstein

The Story Behind the Time Painting: Mining Town

(Time Paintings – Lewis Rubenstein Artist)

23 June 2022, Ottawa, Canada

Unknown Siblings

Between parents and children there are always mysteries, things left unsaid. Before the birth of a child, each parent has a separate and distinct life–travels, loves, loses and sometimes near death experiences. Some of these stories travel with a parent to the grave. Some are gladly told to children or young adults, but some are never shared because a parent does not imagine that their offspring would be interested. Such was the case with my late father, Lewis William Rubenstein, who never talked about living in a dormitory with a jovial group of miners from the Case Verde copper mine in Jerome, Arizona.

My father had died in June of 2003, and I had begun to go through the many watercolors, drawings, sketch books, and oil paintings in the art room in my sister Emily’s house on the shores of Lake Champlain. My brother-in-law Paul had said to me, “There are some amazing drawings down there. You have to see them.”

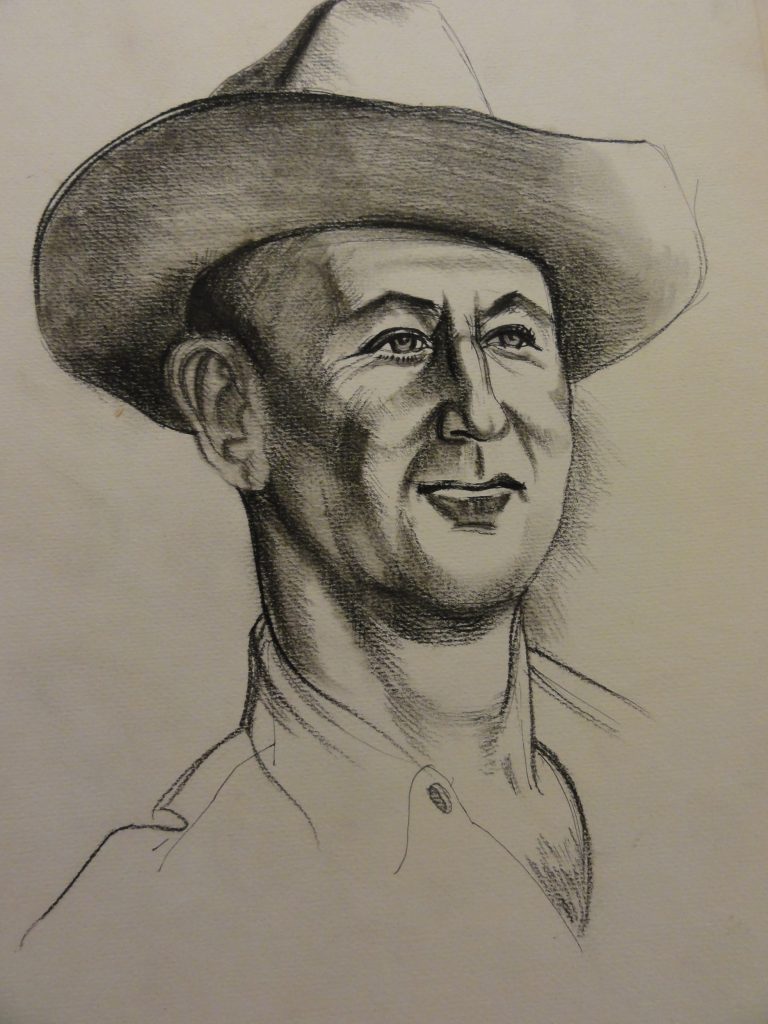

Now, I was alone with the sketch pads. I read in the inside cover of the warn sketch book, “If found, please return to Lewis Rubenstein, General Delivery, Jerome, Arizona.” The time was 1937. I leafed through the warn pages. There were miners in a deep shaft, holding a giant drill. There were miners washing off soap in the shower, playing cards. There were detailed drawings of a of a rock drill. There were miners leaning out of a train car. There was one color sketch that took my breath away.

Who was this man? How did Lewis meet him? I did not need to ask myself why Lewis was sketching this face. A face like that of the miner demanded that it be captured in pencil and paper. I just sat back visualized my father sketching the strong face of the miner. My father would have been wearing a canvas hat with a wide brim, sitting on the three-legged stool in his knapsack, sketching the miner. But why did I only meet this man after my father had died?

These faces were new to me because the painter I had grown up with mostly painted watercolors of the Hudson River, but not the faces of miners. My father’s drawings from the 1930s were never displayed on the walls of his studio at the back of our home, or on the living or dining room walls. I had never seen the strong face of the copper miner. Why I wondered, had my father left behind this striking realism, moving on the landscapes. Perhaps these drawings were a product of the times, a time of depression, strikes and hardship that forced an artist to take a stand on social issues. When my father had been with the miners in Jerome, Arizona, Steinbeck had been travelling with the Okies in California, Pete Seeger and Woodie Guthrie had been riding the rails.

I began to ponder the improbability of a Harvard graduate from a middle class, Orthodox Jewish home living with the miners in the sketches, sharing their lives, and to some extent their sorrows in September 1937. I pictured my father, a deeply freckled young man with a bushy shock of brilliant red hair. He was 29 but he looked like a college freshman.

Wandering Across America in 1937

“After graduating from Harvard University in 1930, I spent two years studying and painting in Europe. In 1932 I returned to America at the height of the Great Depression. Wanting to experience the hard times which the country was going through, I joined a hunger march to Washington that winter. We went in buses that were crammed full of black and white men and women together. We slept on floors in churches, union halls, and on the street. Once, after sleeping in one of those places at night, were beaten up by the police as we were running downstairs. Outside of Washington, we slept on the cold highway. We had fires at night from any wood we could pick up from the hills overlooking the railroad tracks. The march had an influence on my artwork.[1]

Lewis made sketches of what he saw as he followed the Hunger Marchers from Buffalo in a march that culminated in the Capital Building on December 4, 1932.[2]

Four years later Lewis began his travels across America,

“After I finished the frescoes in the Germanic Museum, I wanted to draw and paint all over the country, particularly industrial and labor subjects. I started out first to Washington to see some friends there. A number of them worked on the La Follette Committee which was investigating the business community’s violation of organized labors’ civil liberties. My friends were in touch with industrial and union activities all over the country, and they referred me to people down South and suggested places to go. I went to Virginia and the Carolinas, drawing and painting mostly in garment factories. I soon headed to the Tennessee Valley Authority and then to Birmingham and New Orleans.[3]”

In Washington, D.C. Lewis stayed with his close friends from Harvard, Dan Margolies, and Allan Rosenberg. Both had graduated from Harvard Law School and immediately headed to Washington to be part of the New Deal. These close friends helped Lewis chart his path across America.

“After travelling in the South, I went back to Buffalo, New York , with my family. There I bought a secondhand Ford and headed west to see the country. The first destination was Cleveland, to draw in the Bethlehem Steel plant located there. It was the time of the great steel strikes of the 1930’s and bitter feelings ran deep. I spent some time drawing in the plant. When I came out, the strikers grabbed me. They insisted that I was a company informant and spying on the men… Finally, the biggest of the leaders just tore up all my drawings and told me to get out of town and never come back again. I spent the night sleeping out on the beach on the shore of Lake Erie; I couldn’t stay in anyplace in town.”[4]

Lewis lived in a two dimensional world, where through twisting and disguising perspective he could transform three dimensions into the two dimensions of a pen and ink drawing. Wherever Lewis went, he had a sketch pad. His is modus operandi was always the same. He saw, he framed, he composed in his mind and then he sat down to sketch.

When he sketched, or painted, Lewis was impervious to hunger, heat, cold, fear, longing, lust or any other human emotion. Lewis was totally focused on conveying a three dimensional image, rich with color, and texture onto the paper, with deft, highly controlled strokes of his pencil. He frequently looked up from his drawing to the subject, then darted back to the paper. Lewis was unaware of others, anything around him. He was focused on the visual image in front of him. Invariably Lewis would be surrounded by an audience. This he never noticed. No challenge was insurmountable when Lewis was following a visual image.

Lewis had walked into the Little Steel Strike of 1937 that had pitted steel workers represented by the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) against smaller steel manufacturer companies such as Republic Steel in the Cleveland area. Workers had gone on strike over low wages and poor working conditions. In the past, when workers had gone on strike, they had left the factory and picketed outside the factory. The owners often hired new workers, or “scabs” who crossed the picket lines worked in the factory. What had happened in Cleveland was something new, a sit down strike. The workers stayed at their work stations. They did not move. This made it harder for the owners to bring in scabs. The workers, sitting down, were always in the way.

After Cleveland, Lewis kept moving across the country. Jerome Arizona must have stopped him in his tracks. No one in 1937, or for that matter, at any time in the history of Jerome, would or could say that all roads lead to Jerome, Arizona.

To be continued in Part II, the next post on this blog.

[1] “Travels with Sketch Pads and Paint Brushes: the 1930’s Labor Artwork of Lewis Rubenstein,” in Labors Heritage, Vol. 7 No. 3 (Winter 1996). This journal was founded in 1989, and was published quarterly by the AFL-CIO’s National Labor College until 2004. The twenty page article about Lewis Rubenstein, profusely illustrated with his artwork, is based on an interview with the artist and acknowledges his unstinting support for labor’s cause.

[2] See the sketches of Lewis Rubenstein in the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Museum at http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/images/detail/lewis-rubensteins-sketchbook-documenting-hunger-march-to-washington-dc-8065.

[3] Op. Cit.

[4] Ibid.