Mining Town: Part II

Lewis William Rubenstein and the Art of the 1930s

22 June 2022, Ottawa, Canada

By

Daniel Blake Rubenstein

Cleopatra Hill, Verde Valley, Jerome, Arizona

Jerome is about 100 miles (160 km) north of Phoenix along State Route 89A between Sedona and Prescott. To find this small speck in a vast desert wasteland, Lewis must have been actively looking for this spot. Lewis would talk to anyone he met when he was searching for visually interesting material. Lewis was a personable fellow who was interested in all of humanity in all its diverse forms and costumes. The one thing that no one would have told Lewis was that Jerome was the place to find work. In 1937 Jerome was hurting as the price of copper had again plummeted. This was a time or another economic backslide, when unemployment was again on the rise. The effects of the early New Deal were wearing off.

Jerome exists in Black Hills of Yavapai County. Founded in the late 19th century on Cleopatra Hill, the town overlooks the Verde Valley. Jerome is more than 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above sea level.

From the beginning, Jerome was a wild town with minimal law enforcement, building codes, or real government. It was so wild that it earned the title “The Wickedest Town in America.” Jerome’s reputation for gambling, alcohol, drug abuse, gun fights, and other assorted mayhem only grew after it incorporated. The population grew by leaps and bounds through the next few years, and, when World War One came, the price of copper soared and, along with it, the number of miners needed to tear the ore out of the mountain. They came from Mexico, China, and all over Europe – Irish, Italian, Hungarian, Polish, Slovakian, German – to work the mines in the unlikely town of Jerome, Arizona which clung stubbornly to the side of a mountain 5,000 feet in the air.

But, as with almost all the other boomtowns, the good times finally came to an end for the town of Jerome. High grade ore became scarcer and harder to dig out of the mountain. The price of copper fell. And in 1929 the Great Depression began. As quickly as it built itself into a money producing machine, Jerome fell into the depression along with the rest of the country. The mines closed in 1930. There are few records of the town during this period. People were hanging on with their hopes and prayers. There was no other real employment for a hundred miles in any direction. Finally, in 1935 Phelps Dodge bought up a majority of the mining rights in and around Jerome. They decided to blast the ore out of the mountain, creating a huge open-pit just to the north of town. The mining would continue until 1938.

This was the scene that Lewis drove into in his travels during 1937. For Lewis this would have been perfect. There was an abundance of interesting people to sketch and paint, all piled up on top of each other with nowhere else to go and nothing else to do but pose for the redhead, whether they wanted to do so or not. But this human soup was only part of the attraction. There was the setting, Cleopatra Hill.

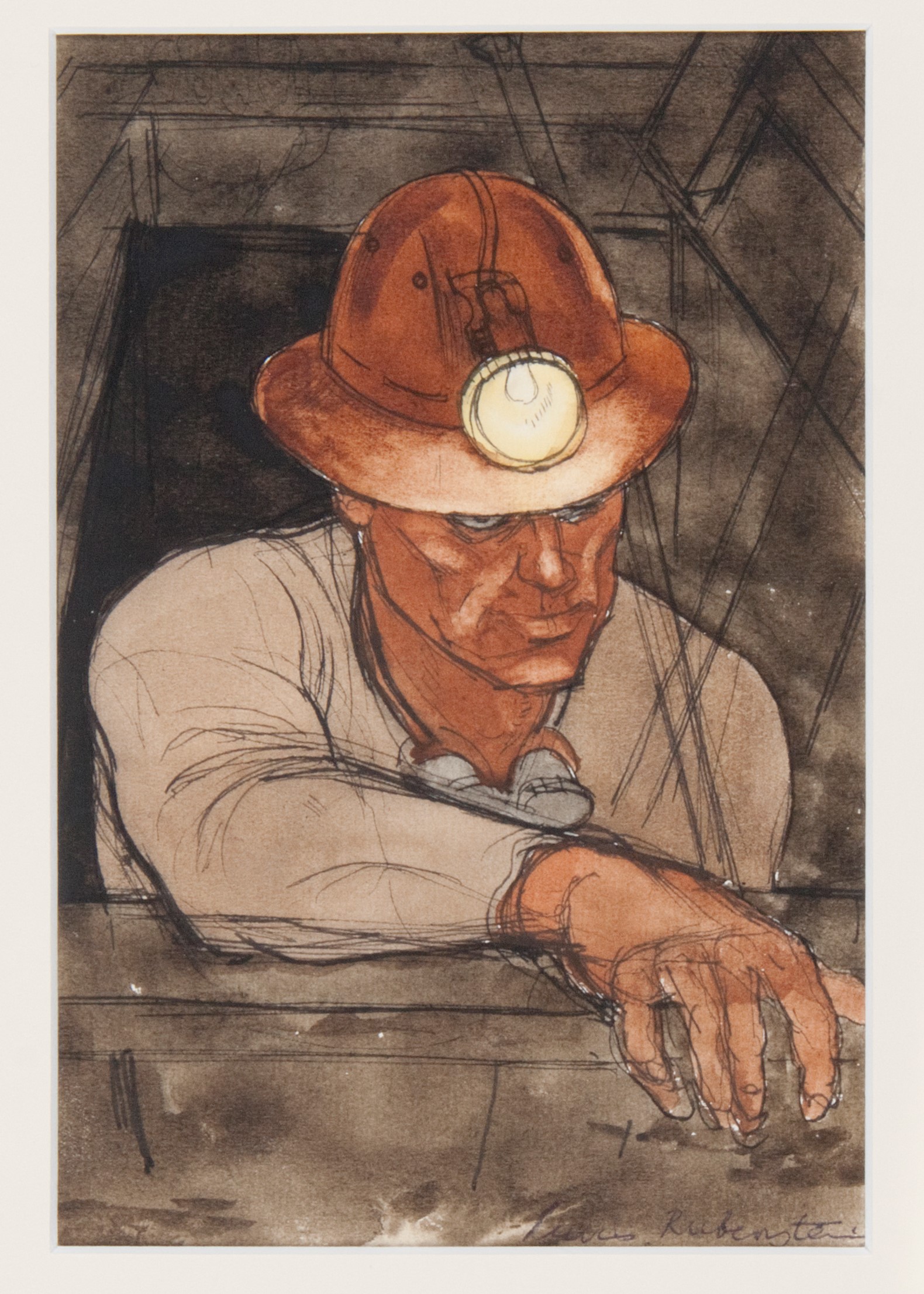

Lewis always loved what he called people in nature. He said his favorite artist was Breughel who placed people in nature. Lewis had found a stark natural setting, a backdrop against which to draw the men who worked the mine. This is how Lewis described his experience with the miners of in his unpublished autobiography, Threads of My Life:

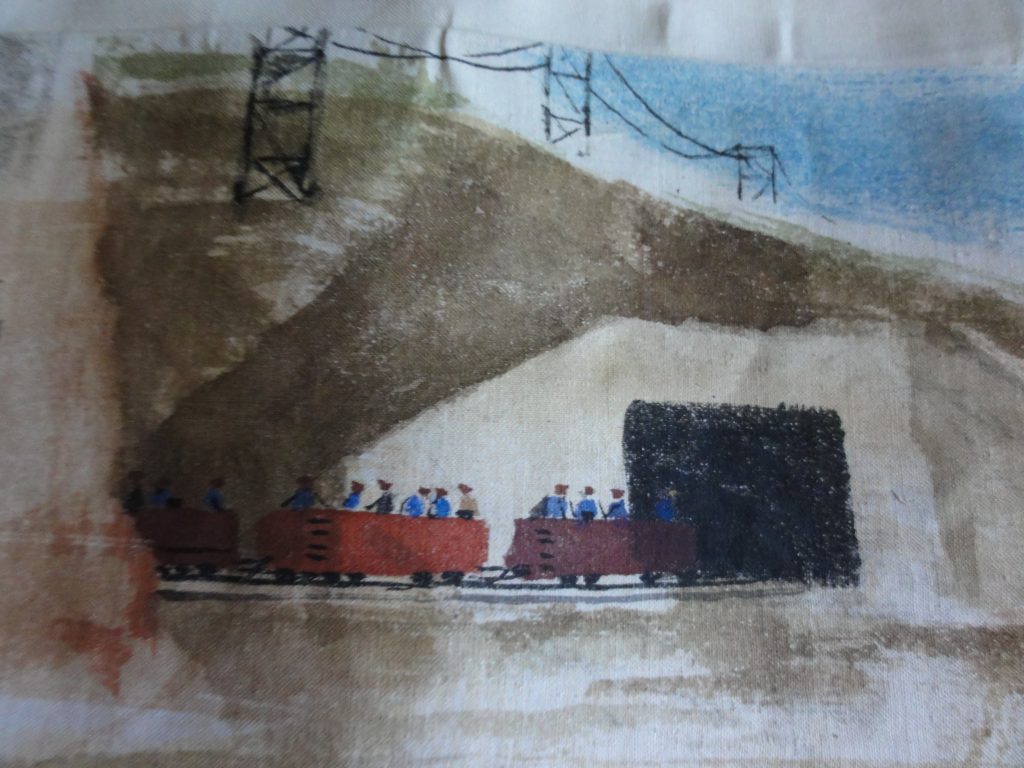

“It was a copper-mining town, called Jerome, on top of the mountain, overlooking the Verde River Valley, a beautiful are. In August and September 1937, I used to go into the mines or around town every day and sketch. The mines themselves were fascinating. I would go down with the men, either on flat cars or on elevators, down to as low as the 5,000 foot level and they let me work fairly freely around there.. I got to know the miners. At nights I used to go around to where the men were all drinking and playing cards. I used to draw them there and talk with them. They were a very jolly, friendly bunch; all were from Mexico. The unmarried miners lived in a dormitory. The woman would come up to the mine entrance to wait for casualties. I made a lot of drawings and paintings in Jerome. Based on my experience and working in the copper mines, later, in 1948, I made the Time Painting ‘Mining Town.’ Time Painting is a form I originated. It is a continuous scroll I paint in watercolor on a linen scroll about thirty feet long. I design it to be seen moving through the window of a special viewing frame.”

(See Threads of my Work – Lewis Rubenstein Artist)

Curious about Jerome in 1937, I corresponded with the Jerome Historical Society who provided me with black and white photographs of the era. I compared these photos to some of the sketches in in the tattered notebooks, wanting to see how the artist had transformed the gritty reality of mining into the breathtaking sketches that are part of my father’s artist legacy.

There were pictures of the men drinking, cleaning up after a day of work. My father could get along with anyone—he was so gentle, unassuming, and above all so non-threatening. I can picture my father in the showers, watching poker games and thoroughly enjoying every moment of his life in Jerome. It was as though a month in the mines had been included in his destiny, when he had left the hospital in Buffalo, but he and his father Emil, just did know it then.

The images of the miners in Jerome Arizona must have stayed with Lewis long after 1937, because they again surfaced a decade later when Lewis conceived of telling the story in his first Time Painting. During the intervening period Lewis had served in Navy camouflage, married Erica Beck Rubenstein, an art historian with a Ph.D. from Radcliffe College, and rejoined the Vassar College Department of Art. But when the miners again appeared in his work, the artist’s style had changed. The miners were in the story but the breathtaking, sharp realism of the art of the 1930s was gone.

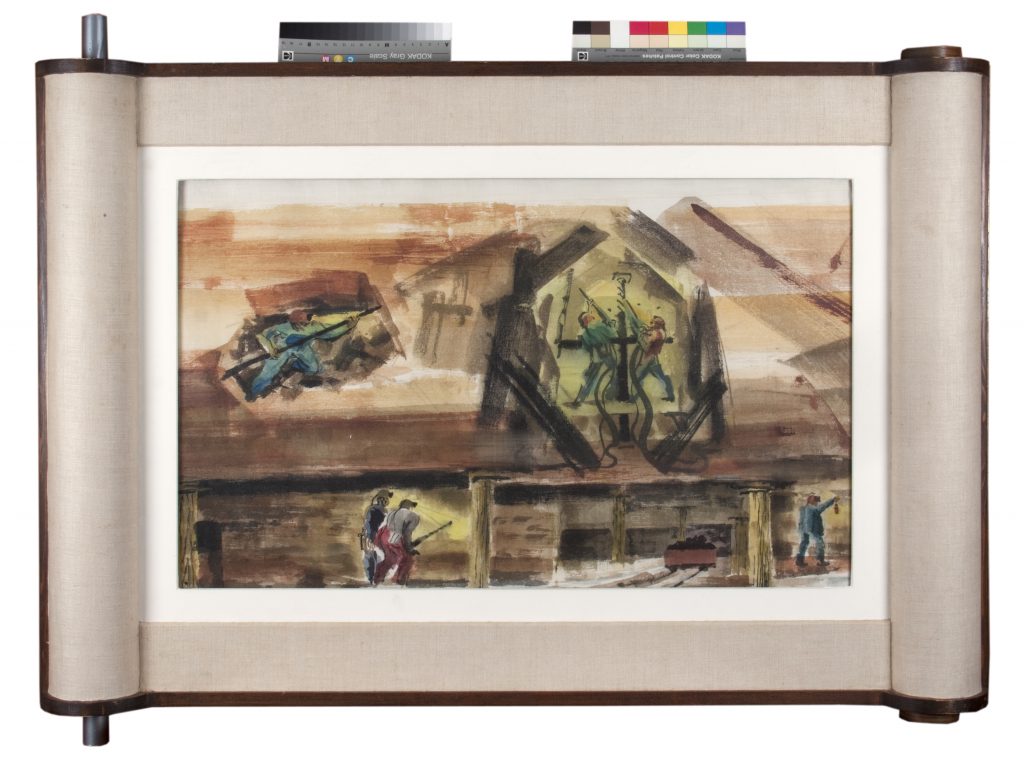

The Invention of the First Time Painting, Mining Town

According to Rubenstein, “The artist’s job is, I believe, to give form to his own view of life and thereby to touch the spirit of others.” Lewis saw cinema as the supreme or ultimate art form because it involved all the arts—drama, writing, music and the visual arts in the form of cinematography.

Two interconnected threads had Lewis to conceive of a painting that moved over time and space. The first thread was the Jewish Torah Scroll. The second thread was that of the long oriental pen and ink scrolls that Lewis had seen in the Gardner Museum in Boston.

“The third thread running through my work is my use of the horizontal scroll form. This started early, too. As a kid I liked to do continuous drawings on rolls of paper with colored crayons, then Id run them through a cut-out opening in a box in front of a lamp. My first real introduction to the great Far Eastern scrolls was in the Boston Museum. Arthur Pope used to take our Harvard Fine arts iA class to the Museum. He communicated a tremendous feeling for such scrolls as “The Burning of the Sanjo Palace,” the Chinese landscape scrolls, Dragon scrolls and others. The impact of these Far Eastern scrolls had been percolating in my mind for a number of years while I was doing murals. Along about 1948 I got the idea of combining the horizontal scroll form with the framed picture. The impetus was to develop a sustained visual theme in time as well as space—to do something like music. I developed what I call Time Painting. This is a continuous scroll paining designed to be seen moving through the window of a special viewing frame…I’ve done documentaries, such as Mining Town.”[1]

A Time Painting viewer consists of a carefully crafted wooden picture frame set between an area to hold two large rollers. The lower piece cradles the scrolls. The top piece, on hinges, closes over the scrolls. The top portion of the viewer is covered in linen. There is a matted framed opening, the heart of the special viewers that Lewis designed.

Lewis wanted viewers to experience what he had seen when he had first come to the Cleopatra Hills. As in all his subsequent Time Paintings, Lewis would phase into a scene, or setting, almost the way a cinematographer would capture a wide angle view of a setting. Then Lewis would focus on the hills themselves.

Then the artist wanted to position the open pit copper mine.

Now the artist focusses on his real interest, the miners, with whom he lived and travelled underground into the depths of the mine. But here the style and depiction is more abstract, compared to the stark realism of the artist’s drawings in 1937.

Once Lewis got an image in his mind, he never let go of it. It was as though an archetypical image had been seared into his brain, never to leave him. Such an archetypical image was that of a miner with a drill underground or the image the woman with a child on her back in Oaxaca Mexico.

The artist devotes multiple images to the drilling, which was centreal to the work.

Then there is an accident. I wondered whether Lewis saw a mining accident or imagined one.

Here the artist’s style is more realistic, more similar to the stark lines in his original drawings. There are the wives waiting for the injured miner to be brought out of the mine.

In the last image, again the view is that if a cinematographer, phasing the camera away from the mine, into the arid lands. The burro is a light touch.

In some ways, the sketches of Jerome and the Mining Town Time Painting are some of my favorite works. The images are inspiring, noble, yet so real. Our family did notwant these wonderful works living in the art storage room, overlooking Lake Champlain. We wanted the works to be preserved in museums, by curators. We wanted young art students to see the works.

Accordingly we donated the Mining Town Time Painting to the Mercantile Museum, of the University of Missouri in St. Louis. A well known collector and friend of my fatather, Bruce Feldecker, had already donated his wonderful collection of my father’s art of the 1930s to the Mercantile Museum (www.umsl.edu/mercantile ).[2]

We also gave some of the sketches to Vassar College, where my father taught studio for thirty five years.[3] Recently we gave some sketches to Tufts University, my alma mater.[4]

A question for these curators, and others who may view the works could be the artist legacy of Lewis William Rubenstein. Perhaps the views of my late mother, Erica Beckh Rubenstein might be informative.

About three years before Erica died in 2014, I asked her, “Is Dad a great artist?”

She hesitated, struggled with the question. In an effort to bridge to her world, to creat a link, as she was suffering from dementia, I said, “Well Mom, who is a great artist?’

Without hesitation she replied, “Well Rembrandt was a great artist.” She thought for a moment then said, “I guess your father was a very good artist.”

[1] Lewis Rubenstein: Retrospective Exhibition catalogue, Vassar College Art Gallery, May 5 through June 7, 1974.

[2] Contact: Julie Dunn-Morton, St. Louis Mercantile Library at UMSL, 1 University Blvd, St. Louis MO 63121, 314-516-6740 (office), dunnmortonj@umsl.edu.

[3] Contact: Patricia Phagan, Ph.D.,The Philip and Lynn Straus Curator of Prints and Drawings, Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Box 703,124 Raymond Avenue, Poughkeepsie, NY 12604, 845-437-7582 office, paphagan@vassar.edu.

[4] Laura McDonald, Manager of Collections, The Aidekman Arts Center, Tufts University, 40 Talbot Avenue, Medford MA, 02155, 617-627-3518, Laura.McDonald@tufts.edu.